The conversation is starting to shift. More and more, the biggest objection we hear from investors and CISOs isn't accuracy anymore, it’s liability!

The narrative goes like this: “Connecting an LLM to our enterprise database is a privacy nightmare. We can’t have a stochastic model reading our PII, hallucinating data leaks, or ignoring our access controls.”

They are right to be worried about a raw, unbridled LLM connection. But they are wrong about the architecture.

Treating Text-to-SQL as "just a chatbot hooked to a database" is a catastrophic architectural error. In an enterprise setting, the LLM is not a database administrator, it is a translator. And like any untrusted component in a secure stack, it must be wrapped in deterministic guardrails, zero-trust principles, and rigorous state validation.

This essay demystifies how we (and the industry's most robust systems) architect safe "Chat with Your Data" pipelines. It turns out security isn't just a patch; it's actually the key to higher accuracy.

The Architecture of Control

Secure Text-to-SQL relies on a simple premise: The model should never know enough to be dangerous.

We don't just "prompt" the model to be safe. We starve it of the information it doesn't need, and we handcuff it when it tries to act. And we assume prompt injection is possible; That means every user message, and any retrieved documentation, is treated as untrusted input. Prompts can steer behavior, but policies live in deterministic gates and database enforcement, not in “please don’t” instructions.

Here is how that works in production.

1. Dynamic Context & The "Need-to-Know" Schema

In our architecture, we implement Role-Based Schema Pruning. When a user logs in, we identify their role (e.g., Marketing Analyst). Before the LLM ever sees a prompt, a retrieval layer selects only the tables relevant to that specific user’s domain.

- The Mechanism: We maintain a vector index of table definitions tagged with access roles.

- The Result: If a Marketing user asks a question, the model effectively "forgets" that the HR_Comp_Table even exists. It cannot query what it cannot see.

This isn’t even just for Security. By scoping the schema to what the user can actually access, you reduce schema noise, cut prompt bloat, and lower the odds of schema-based hallucinations, often increasing SQL accuracy, while reducing costs and latency.

2. Column-Level Omission (The Invisible Wall)

Table-level access isn't granular enough. You might want a manager to see the Employees table but not the SSN or Salary columns.

We handle this upstream of the model. When we construct the system prompt, we filter the DDL (Data Definition Language) to strip out sensitive columns entirely.

- Scenario: A user asks, "Show me the highest paid employee."

- Model Reality: The model looks at the provided schema for Employees, sees only Name, Department, and Tenure. It sees no Salary column.

- Outcome: The model halts and asks for clarification, or generates a query based on Tenure (which we can catch via feedback). It physically cannot write a valid SQL query for a column it doesn't know exists.

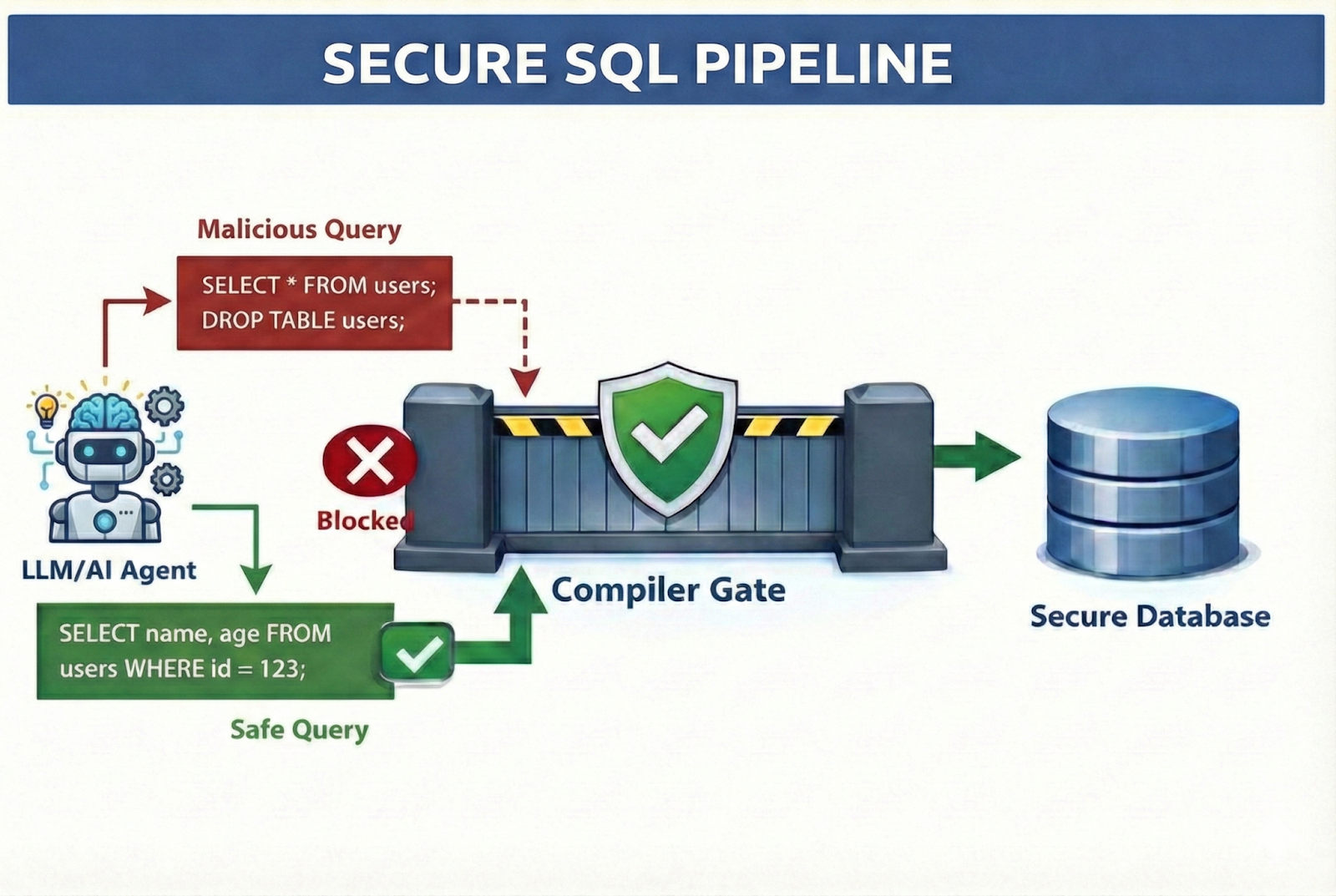

3. Abstract Syntax Trees (AST) & The Compile Gate

This is the most critical layer, and we treat it as a two-stage defense system. We never simply execute what the model outputs.

Stage 1: The AST Policy Enforcer

First, we parse the raw text into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) before it ever touches the network. This allows us to perform structural analysis against the specific user’s permissions:

- Granular Column Validation: This is the most critical check. We traverse the tree to verify that every referenced column in the SELECT, WHERE, and JOIN clauses belongs to the allow-list for that specific user. Even if the model hallucinates a hidden column (like user_password), the AST catches it immediately because it is not on the list.

- Destructive Command Blocking: We traverse the tree to ensure no DROP, ALTER, or UPDATE nodes exist.

- Policy Injection: We mechanically insert non-negotiable business rules directly into the query structure. Whether it’s enforcing tenant isolation, restricting data to specific time windows, or applying global status filters, the AST ensures these constraints are applied programmatically. The LLM’s output is treated as a draft; the code ensures the final query complies with enterprise governance.

Stage 2: The SQL Compile Gate (The "Dry Run")

Once the AST is satisfied, the query moves to the SQL Compile Gate. This is where we validate reality against the database engine without actually running the query.

We open a connection to the database and run the query through specific non-executing modes (like SET PARSEONLY ON, SET SHOWPLAN_XML ON, or sp_describe_first_result_set). This asks the database engine: "If I were to run this, would it work? Do these columns exist? Does this user have permission to map them?"

If either the AST or the Compile Gate flags a violation, the query is rejected before execution. We then trigger a Feedback Loop: The system returns a sanitized error to the model (e.g. "Column 'Salary' does not exist or is unauthorized"), allowing it to self-correct without ever leaking data.

4. Execution Identity: RLS is the Final Boss

Prompt engineering is not security. Governance must live in the database layer.

When our system finally executes a query, it does not connect as a generic root or admin user. It connects using Identity Propagation. If Jane Doe asks the question, the query runs as db_user_jane.

This leverages native Row-Level Security (RLS) policies (FILTER/BLOCK predicates in SQL Server or PostgreSQL). Even if the LLM writes a query like SELECT * FROM Sales, the database engine itself invisibly applies the predicate WHERE Region = 'EMEA', because that is the only data Jane is allowed to see.

Metadata vs. Data: The Zero-Trust Insight

A key realization for secure Text-to-SQL is that the model almost never needs to see the actual data.

The model needs metadata: table names, column types, and foreign key relationships. It acts as a logic engine, not a storage engine.

- High Cardinality Columns: For columns like Customer_ID, the model only needs to know the format, not the values.

- Low Cardinality Columns: For columns like Status (e.g., 'Shipped', 'Pending'), we inject distinct values into the prompt so the model knows the specific vocabulary.

By decoupling metadata (which goes to the LLM) from actual data (which stays in the DB), we ensure that PII never traverses the API boundary during the reasoning phase.

A Note on Petalytics

We built Petalytics (request early access) to operationalize this layered defense. It is not just a "text-to-SQL" tool; it is a governance layer for your data warehouse.

- Role-Based Context Injection: Your Marketing team will never accidentally query Legal's tables.

- AST-Driven Guardrails: We parse before we execute. Malicious prompts or hallucinations hit a syntax wall, not your database.

- Native RLS Integration: We respect the security policies you’ve already built in Snowflake, Databricks, or SQL Server.

- Compilation Feedback Loops: If a user tries to access unauthorized data, the model is guided to politely decline, citing "insufficient access" rather than "data not found," building trust through transparency.

Implementation Checklist

- Define Access Scopes: Map your database roles to specific subsets of tables (Schema Pruning). Do not rely on "hope" that the model ignores the User_Secrets table.

- Sanitize the DDL: Write a pre-processing function that strips sensitive columns from the schema context passed to the LLM.

- Implement AST Parsing: Use libraries like sqlglot or pg_query to parse generated SQL into an AST. traverse the tree to verify that every accessed object is on the user's allow-list.

- Enforce Read-Only Connection: The database user for the LLM application must have strictly SELECT privileges, preventing any prompt-injection attacks from modifying data.

- Enable Database RLS: Ensure your database applies row-level filtering based on the session user. This acts as a fail-safe if the LLM context leaks.

- Audit the Metadata: Ensure the column descriptions and value examples you provide to the LLM do not themselves contain PII.